Balochistan, the largest province of Pakistan by area, has a history deeply intertwined with tribal sovereignty, colonial diplomacy, and nationalist resistance. Often at the periphery of the subcontinent’s dominant political narratives, Balochistan has nonetheless played a central role in debates about statehood, self-determination, and federalism. Its brief moment of declared independence in 1947, just before Pakistan’s creation, remains a flashpoint in contemporary nationalist discourse and continues to fuel ongoing tensions between Baloch separatists and the Pakistani state.

Ancient Roots and Tribal Traditions

Balochistan’s history dates back thousands of years. The Mehrgarh civilization, one of the earliest known farming settlements in South Asia, flourished in this region around 7000 BCE. Situated at the crossroads of Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East, Balochistan has historically served as a trade corridor and cultural melting pot.

Over centuries, the region became home to Baloch, Brahui, and Pashtun tribes, whose social structures centered around tribal confederations, clan loyalty, and nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles. Unlike centralized monarchies in other parts of South Asia, Balochistan was ruled through decentralized power, with tribal sardars (chiefs) exercising considerable influence.

Khanate of Kalat and Pre-Colonial Sovereignty

In the 17th century, the Khanate of Kalat emerged as a semi-sovereign political entity, uniting several Baloch tribes under the leadership of the Ahmadzai dynasty. The khanate established diplomatic and trade ties with neighboring powers such as Persia, Afghanistan, and Sindh. It maintained a level of autonomy even during periods of external pressure, often negotiating rather than waging war.

The Khanate’s political structure was a federation of semi-autonomous tribes bound by allegiance to the Khan. This historical background has been central to Baloch nationalist claims that Balochistan was a sovereign entity long before British colonization or Pakistani accession.

British Influence and the Treaty with Kalat

Balochistan came under British influence in the mid-19th century, as Britain sought to secure its Indian empire’s northwestern frontiers during the “Great Game” rivalry with Tsarist Russia. Rather than outright annexation, the British opted for treaty-based arrangements, recognizing Kalat as a princely state but assuming control over its foreign affairs and defense.

The Treaty of 1876, signed by Khan Khudadad Khan and British officials, effectively cemented Kalat’s status as a semi-independent princely state under British suzerainty. Several regions, including Quetta, were leased to the British, while the Khan retained internal governance.

This treaty-based relationship is often cited by Baloch leaders and historians as evidence that Kalat was a legally distinct entity and not a colonial province like Punjab or Sindh — a distinction that would prove pivotal in 1947.

1947: Declaration of Independence by the Khan of Kalat

When British India was partitioned in 1947 into India and Pakistan, princely states were theoretically given three choices: join India, join Pakistan, or remain independent — subject to practical considerations like geographic continuity.

On August 11, 1947, three days before Pakistan’s independence, the Khan of Kalat, Mir Ahmad Yar Khan, declared that Kalat would remain an independent state, based on its treaty obligations and unique status. The Khan argued that Kalat had never been part of British India and had the right to assert sovereignty. This declaration was supported by the Kalat State National Party (KSNP), the region’s dominant nationalist political party at the time.

In the weeks that followed, Kalat entered negotiations with the newly-formed Pakistani government, proposing a treaty of friendship and mutual cooperation rather than formal accession. For a brief period, Kalat operated as a de facto independent state, conducting its own affairs.

Forced Accession and Controversy in 1948

Despite Kalat’s declaration of independence, the Pakistani government — led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who had earlier served as Kalat’s legal adviser — strongly opposed the idea of an independent Baloch state. Strategic concerns, particularly Kalat’s location near Iran and Afghanistan, compelled Pakistan to seek its integration.

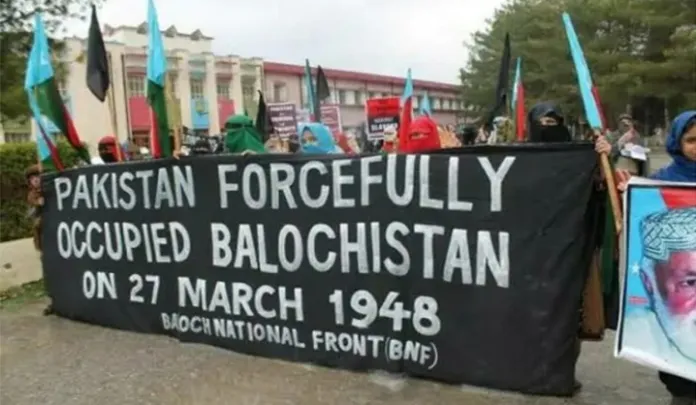

On March 27, 1948, under mounting pressure, the Khan of Kalat signed the Instrument of Accession, merging his state with Pakistan. However, multiple sources — including accounts from the Khan’s own family — suggest that the decision was made under duress. The Kalat State National Party denounced the move, claiming it lacked legal and popular legitimacy.

Shortly afterward, Prince Abdul Karim, the Khan’s younger brother, led the first armed rebellion against the Pakistani state from the mountains of Balochistan, declaring the accession invalid and calling for continued resistance. Although the rebellion was eventually crushed, it laid the foundation for decades of insurgency and nationalist struggle in the region.

Waves of Resistance and Separatist Insurgencies

Since 1948, Balochistan has experienced five major insurgencies:

- 1948–49: Led by Prince Abdul Karim, opposing forced accession.

- 1958–59: Sparked by the imposition of One Unit policy and the arrest of the Khan of Kalat.

- 1962–63: A short-lived uprising fueled by increasing centralization.

- 1973–77: The largest and most violent insurgency, involving thousands of guerrillas after the dismissal of the Balochistan government by Prime Minister Bhutto.

- 2004–present: An ongoing insurgency marked by attacks on security forces, targeted killings, and sabotage of energy infrastructure.

These uprisings have been driven by demands for greater autonomy, control over natural resources, protection of Baloch culture and language, and in many cases, complete independence.

Economic Marginalization and Resource Exploitation

A key grievance among Baloch nationalists is the alleged exploitation of the province’s natural wealth by the federal government. Balochistan is rich in natural gas, coal, copper, and gold, yet remains Pakistan’s poorest province, with high levels of illiteracy, unemployment, and underdevelopment.

Projects like the Sui gas fields and the Gwadar port have been touted as symbols of national progress but are viewed by many locals as examples of exploitation, where profits benefit distant provinces while the local population remains disenfranchised.

Human Rights Violations and International Attention

Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and UN Working Groups have documented widespread abuses in Balochistan, including:

- Enforced disappearances of activists and students.

- Extrajudicial killings of suspected separatists.

- Suppression of media and academic freedom.

- Militarization of civilian spaces.

On the other side, insurgent groups like the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) and Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF) have been accused of targeting civilians, particularly non-Baloch settlers, and carrying out bombings, further complicating the conflict.

Geopolitical Dynamics and Regional Interests

Balochistan’s geopolitical significance has grown in recent years due to its proximity to Iran, Afghanistan, and the Arabian Sea, as well as its central role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), with Gwadar Port as a major node, has raised concerns among Baloch activists about land dispossession and demographic shifts.

Additionally, Iran’s Baloch minority has raised fears in Tehran of cross-border militancy, while India has occasionally voiced support for Baloch human rights, much to Pakistan’s irritation.

The Unfinished Struggle for Recognition

More than seven decades after the forced accession of Kalat, Balochistan remains a land of unresolved tensions. The brief moment of declared independence in 1947 is not merely a historical footnote — it is a rallying point for a generation of Baloch youth who see themselves as victims of historical injustice.

While the Pakistani government emphasizes national unity and development, critics argue that without addressing historical grievances, respecting provincial rights, and ensuring genuine political inclusion, the cycle of rebellion and repression will persist.

As the world grows more attentive to movements of self-determination, Balochistan’s case stands out as one of South Asia’s most enduring and complex struggles — a story of sovereignty denied, identity suppressed, and resistance that refuses to fade.

Balochistan 2025: A Province on Edge Between Conflict, Control, and Change

Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest and most resource-rich province, remains a region marked by contradictions — vast natural wealth alongside deep poverty, strategic importance alongside political alienation, and ambitious development plans alongside persistent insurgency. In 2025, Balochistan continues to be both a focal point of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and a hotbed of nationalist resistance. While Islamabad pushes forward with infrastructure and security efforts, many Baloch voices warn of marginalization, suppression, and an unfinished struggle for autonomy.

Security Situation: Persistent Insurgency and Militarization

The security landscape in Balochistan remains tense. Though large-scale operations have reduced the frequency of attacks compared to earlier years, low-intensity conflict persists, particularly in the southern and central regions, including Turbat, Gwadar, Panjgur, and Khuzdar.

Major features of the current security situation include:

- Ongoing insurgency by groups like the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), and Baloch Republican Guard (BRG), which carry out targeted attacks on military convoys, Chinese nationals, and infrastructure.

- Frequent IED attacks, ambushes, and sabotage of railway lines and gas pipelines.

- Counterinsurgency operations by the Pakistan Army and Frontier Corps (FC), often involving aerial surveillance, military checkpoints, and house raids.

- Enforced disappearances and kill-and-dump incidents continue to be reported by human rights groups.

In early 2025, there has been an uptick in violence in the Makran coastal belt, with a surge in attacks targeting projects linked to CPEC, especially the Gwadar Port. The BLA recently claimed responsibility for attacks on Chinese engineers working in the region.

Political Climate: Disillusionment and Fragmentation

The political environment in Balochistan remains fragmented and distrustful of central governance. The Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), which had emerged as a pro-establishment provincial force in recent years, has seen declining popularity due to accusations of corruption and ineffectiveness.

Key developments include:

- Low voter turnout in the last provincial elections, especially in insurgency-hit districts.

- Continued exclusion of nationalist leaders and parties like the Balochistan National Party-Mengal (BNP-M) from meaningful power-sharing.

- Military dominance in political decision-making, particularly in administrative appointments and development fund allocations.

- Recent student protests over campus militarization, fee hikes, and suppression of Baloch identity in curriculum have spread across Quetta, Khuzdar, and Turbat universities.

Despite Islamabad’s emphasis on “mainstreaming” Balochistan, many residents feel politically alienated, pointing to token federalism and lack of genuine local control.

Economic and Development Projects: Progress Amid Discontent

Balochistan is central to Pakistan’s vision of economic modernization, largely due to the Gwadar Deep Sea Port and its role in CPEC. However, the distribution of benefits remains highly controversial.

Highlights of economic activity and challenges:

- Gwadar Port is operational, but locals complain about joblessness, land acquisition without compensation, and lack of clean water and electricity.

- New roads and railway links have improved connectivity, yet rural poverty remains high.

- Natural gas production continues from Sui fields, but the province itself receives less than 10% of the supply, sparking outrage.

- Chinese investment is substantial in mining, particularly in copper and gold reserves (e.g., the Saindak and Reko Diq projects), but little local benefit is visible.

In March 2025, the Gwadar Rights Movement renewed its protests demanding fair treatment, basic utilities, and an end to forced disappearances — drawing wide support from local communities.

Human Rights: Disappearances, Censorship, and Repression

Human rights abuses remain one of the most critical and internationally condemned aspects of the situation in Balochistan.

Documented violations include:

- Thousands of Baloch activists, students, and intellectuals have allegedly been abducted or remain missing.

- The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances continues to receive hundreds of unresolved cases annually.

- Independent journalists face severe restrictions, harassment, and in some cases, violence. Local media outlets have been shut down or warned against covering dissent.

- Freedom of expression in universities and cultural spaces has been curtailed, with frequent bans on student unions and Baloch cultural events.

International watchdogs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and UN Working Groups have repeatedly urged Pakistan to halt enforced disappearances, investigate abuses, and respect the rights of Baloch citizens.

Social Indicators: Education, Health, and Infrastructure Gaps

Despite its size and wealth, Balochistan lags far behind other provinces in key human development indicators.

As of 2025:

- Literacy rate remains below 45%, with female literacy below 30%.

- Many districts have fewer than one doctor per 10,000 people.

- Maternal and child mortality rates are among the highest in South Asia.

- Basic infrastructure like roads, clean drinking water, and internet access is severely underdeveloped outside major cities.

A UNICEF report published in April 2025 called Balochistan “one of the most neglected humanitarian zones in the Asia-Pacific region.”

Rise of Youth Resistance and Baloch Diaspora Voices

Baloch youth, both in Pakistan and abroad, are increasingly vocal. Online campaigns under hashtags like #BalochLivesMatter and #SaveBalochStudents are drawing global attention. Diaspora organizations based in Europe, Canada, and the US are lobbying for international scrutiny of Pakistan’s human rights record in the province.

Meanwhile, young activists in Balochistan are using art, poetry, and digital platforms to highlight the region’s history and resistance. However, many face threats, arrests, or exile.

Conclusion: A Crossroads Between Crisis and Resolution

In 2025, Balochistan stands at a crossroads. While infrastructure projects promise prosperity on paper, the underlying crisis of political legitimacy, human rights, and identity suppression threatens long-term stability.Without a genuine political dialogue, accountability for abuses, and fair resource sharing, Balochistan’s future remains uncertain. The province’s vast deserts, mountains, and ports tell a story not just of riches, but of resistance — a story that Pakistan must address if it seeks peace and unity.

You might also be interested in – Indian Forces Launch Operation Nader Against Terrorists in Tral: Major Blow to Militant Network